10 Reasons Why You Should Learn Julia

Even though it has 1-based indexing.

What is Julia?

Julia is a fairly modern language, developed in 2009 by Jeff Bezanson, Stefan Karpinski, Viral B. Shah, and Alan Edelman who had the idea of designing a language that was free, high-level, and fast. The language was officially unveiled to the world in 2012 when the team launched a website with a blog post explaining the language’s mission. When asked why they named the language “Julia”, Alan Edelman turned down the thought that it was named after the fractal, but claimed that it just came up in a random conversation years ago when someone suggested arbitrarily that “Julia” would be a good name for a programming language. When asked why they created Julia, they claimed that they came from different programming language backgrounds, and loved them all. But they were greedy, and wanted more.

We want a language that’s open source, with a liberal license. We want the speed of C with the dynamism of Ruby. We want a language that’s homoiconic, with true macros like Lisp, but with obvious, familiar mathematical notation like Matlab. We want something as usable for general programming as Python, as easy for statistics as R, as natural for string processing as Perl, as powerful for linear algebra as Matlab, as good at gluing programs together as the shell. Something that is dirt simple to learn, yet keeps the most serious hackers happy. We want it interactive and we want it compiled. — julialang.org

Do we really need another language?

Well, yes. Why, you ask?

Programming languages are used for solving various real world problems, but there is not one language that can solve them all, requiring particular approaches. Some are efficient and have more advantages to use over the others. If we take a look at C for instance, C was the most powerful language there was. Everyone thought C would be the language to end all other languages, but then there came a need for a language which could be used to represent real world problems through Object Oriented Programming (OOP) concepts, which is how C++ was born. So why was Java invented then? People needed something as powerful as C++, but slightly easier to use.

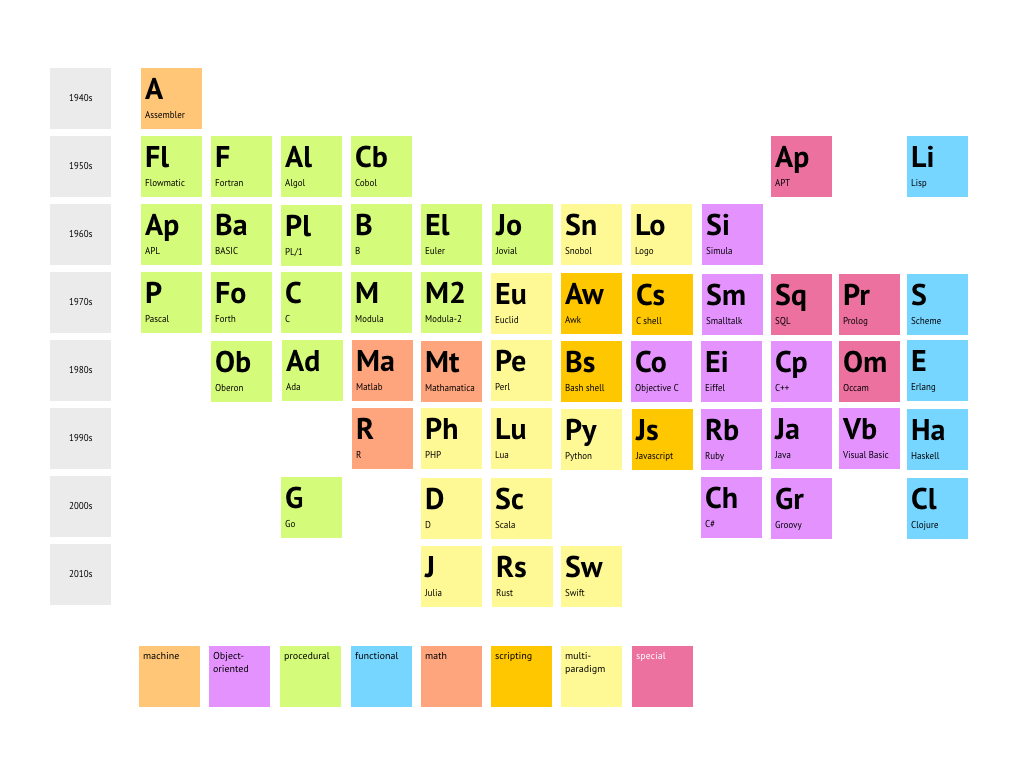

Periodic table of programming languages

Periodic table of programming languages

There will never be the perfect language. Programming languages will never be a finished product, as the world evolves and specific needs change, so will programming languages.

Here are 10 reasons why

1 — It’s blazingly fast right out of the box

Julia was designed from the beginning with high performance in mind without having to sacrifice ease of use like garbage collection, which is a common trade off in languages such as C++. Julia applications can compile to efficient native code for multiple platforms thanks to the LLVM compiler.

Compilers can be extremely efficient when you tell them exactly what to do with your code. Take C for instance, a language which requires you to explicitly define the types of your variables and what you plan on doing with them, such as performing a simple addition. Since the CPU has dedicated hardware for addition arithmetic, it knows exactly what to do and does it extremely well and quickly.

Now take an interpreted language like Python for instance. You give the interpreter two variables to add together, but the CPU has no concept of variables. This means that the CPU must wait for instructions from the interpreter to figure out what these two variables contain. Once that has been figured out, the next step would be to select the right operation. If they are integers, perform integer addition, if they are floats, perform floating point addition, if they are integer and float, convert the integer to a float, then perform a floating point addition. The interpreter has to go through this process every single time an operation is called on a variable. This is what makes Python so slow compared to languages such as C.

Now let’s focus on Julia. If C and Python are on other ends of the spectrum, Julia sits right in the middle. Julia’s compiler doesn’t have to know beforehand what type of variable you’re trying to use, but it cleverly plans ahead whenever you call a function. When a function is called in Julia, the arguments are already known. Julia’s compiler uses this knowledge to figure out the exact CPU instructions necessary for the particular arguments by peeking into the function. Once the exact instructions are mapped out, Julia can execute them very quickly. This is why calling a function in Julia takes long the first time. During this period of time, Julia’s compiler would be figuring out all the types of variables being used and compiles them all into fast and precise CPU instructions. This means that when the same function is called repeatedly, consequent calls run much, much faster.

2 — It solves the two language problem

The industry is currently plagued by what’s called the “two-language problem”. Typically, developers first prototype their application using a slow dynamic language, and then rewrite it using a fast static language for production.

We set out to solve the “two language problem” back in 2009. Much of our progress in parallel computing was thwarted by the fact that while the users are programming in a high-level language such as R and Python, the performance-critical parts have to be rewritten in C/C++ for performance. This is hugely inefficient, because it introduces human error and wasted effort, slows time to market and allows competitors to leapfrog ahead. This two language problem hinders not just researchers, but also quants, scientists, data scientists and engineers in the industry. — Viral Shah, co-founder of Julia Computing

In fact, many companies have toyed around with in-house languages trying to do what Julia does for this very reason, but having an open-source language built on best-of-breed compiler technology is far better.

3 — It excels at technical computing

Designed with data science in mind, Julia excels at numerical computing with a syntax that is great for math, with support for many numeric data types, and providing parallelism out of the box, but more on that last bit later. Julia’s multiple dispatch is a natural fit for defining number and array-like data types.

The Julia REPL (Read/Evaluate/Print/Loop) provides easy access to special characters, such as Greek alphabetic characters, subscripts, and special maths symbols. If you type a backslash, you can then type a string (usually the equivalent LATEX string) to insert the corresponding character. This is great as it allows developers to just derive some equation and directly type it in. For example, if you type:

julia> \sqrt <TAB>

Julia replaces the \sqrt with a square root symbol:

julia> √

Some other examples:

- \Gamma Γ

- \mercury ☿

- \degree °

- \cdot ⋅

- \in ∈

4 — It’s composable

Julia packages naturally work well together. This is thanks to the language’s function composition which makes it easy to pass two or more functions as arguments. Julia has a dedicated function composition operator (∘) for achieving this.

For example, the sqrt() and + functions can be composed like this:

julia> (sqrt ∘ +)(3, 5)

(sqrt ∘ +)(3, 5)

which adds the numbers first, then finds the square root.

This example composes three functions.

julia> map(first ∘ reverse ∘ uppercase, split("you can compose functions like this"))

6-element Array{Char,1}:

'U'

'N'

'E'

'S'

'E'

'S'

This was just a basic example, but Julia makes it easy for packages to communicate with each other. Matrices of unit quantities, or data table columns of currencies and colours, just work — and with good performance.

5 — It does parallel really well

Data has gotten so huge that it has become unpractical to run applications on a single computer. Nowadays everyone is computing big data on multiple nodes in a cluster in order to decrease the execution time by running tasks in parallel, but unfortunately many languages were never designed for this.

Take Python for instance, its interpreter does not do parallel very well as it was designed with the primary assumption that an individual Python script is serial having a single thread of execution. The interpreter makes use of what’s called a Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) which ensures that only a single line of a Python script can be interpreted at a time, thereby preventing memory corruption caused by multiple threads trying to read, write, or delete memory in parallel.

There are of course ways around this issue, such as using the Spark Python bindings PySpark, however not as straightforward as one would hope. PySpark will not run your Python code, but instead use a package called Py4J which will enable Spark to communicate between the Python interpreter and the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). This is because Spark is built on top of Scala which runs on the JVM. This creates a layer of abstraction between your code and the execution of that code. One of the main issues with this is that although you would write Python code, Spark can return errors in Java on code which you would have never written.

Julia was designed for parallelism from the ground-up, and provides built-in primitives for parallel computing at every level: instruction level parallelism, multi-threading, and distributed computing. The Celeste.jl project achieved 1.5 PetaFLOP/s on the Cori supercomputer at NERSC using 650,000 cores.

The Julia compiler can also generate native code for various hardware accelerators, such as GPUs and Xeon Phis. Packages such as DistributedArrays.jl and Dagger.jl provide higher levels of abstraction for parallelism.

6 — Its codebase is written entirely in Julia

That’s right. This is a feature most significant compared to typical dynamic languages. If you can develop applications in Julia, then you can also contribute to Julia. If you need to peek underneath the hood and see what’s up, you’re not going to find C code as you would with Python.

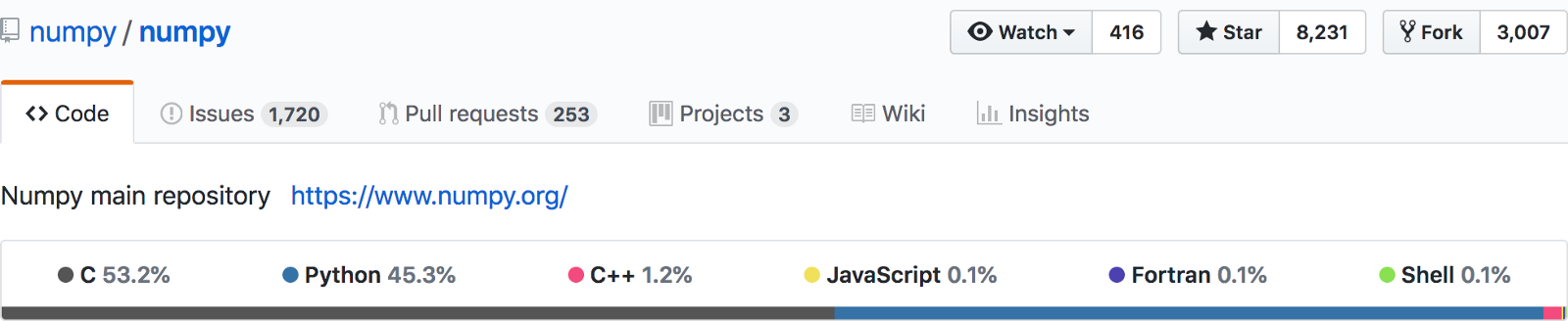

Due to being an interpreted language, Python can be extremely slow compared to older languages such as C/C++ and even newer ones such as Go. However over the years, many Python packages have been optimised to execute at C speed. This might sound great at first, but not when you consider the trade-offs that were taken to achieve this.

Python allows developers to add C extensions. This is great for when you have calculations which could happen several times, allowing further optimisations to be made since such C extensions could be compiled and thus run much faster. Developers can write their code in C++ and call it from within their Python code, giving them a huge performance bump.

However this takes away from the beauty of Python. Python is supposed to be a simple to use, easy to read language. Adding C/C++ to the mixture ruins that, so might as well just use C/C++ in the first place.

Numpy is written more in C/C++ than it is in Python

Numpy is written more in C/C++ than it is in Python

Julia solves this problem however, since it can be as fast as C/C++, without having the need to make such trade-offs. The core language imposes very little; Julia Base and the standard library is written in Julia itself, including primitive operations like integer arithmetic.

7 — Good call support to other languages

Although most things can be done in Julia, if you wish to make use of libraries which have already been written in C and Fortran, Julia makes it easy to do so in a simple and efficient way. Julia was designed with a “no boilerplate” philosophy in mind where functions can be called directly from Julia without any “glue” code, code generation, or compilation, even from the interactive prompt. This is done using Julia’s ccall syntax, which looks like an ordinary function call.

Julia’s external call support does not stop here. Julia can also interface with C++, Python, R, Java, and many other languages, making it possible to even share data between the two languages. Julia can also be embedded in other programs through its embedding API. Specifically, Python applications can call Julia using PyJulia. R programs can do the same with R’s JuliaCall, which is demonstrated by calling MixedModels.jl from R.

8 — It’s dynamic and easy to understand

There exist two types of programming languages, static languages where you’re required to have a type computable before the execution of the program, and dynamic languages where nothing is known about types until run time, when the actual values manipulated by the program are available.

Julia’s type system is dynamic, but gains some of the advantages of static type systems by making it possible to indicate that certain values are of specific types. This can be of great assistance in generating efficient code, but even more significantly, it allows method dispatch on the types of function arguments to be deeply integrated with the language.

The default behaviour in Julia when types are omitted is to allow values to be of any type. Thus, one can write many useful Julia functions without ever explicitly using types. When additional expressiveness is needed, however, it is easy to gradually introduce explicit type annotations into previously “untyped” code. Adding annotations serves three primary purposes: to take advantage of Julia’s powerful multiple-dispatch mechanism, to improve human readability, and to catch programmer errors.

9 — It’s optionally typed

Julia has a rich language of descriptive data types, and type declarations can be used to clarify and solidify applications.

You can define functions with optional arguments, so that the function can use sensible defaults if specific values aren’t supplied. You provide a default symbol and value in the argument list:

julia> function xyzpos(x, y, z=0)

println("$x, $y, $z")

end

xyzpos (generic function with 2 methods)

And when you call this function, if you don’t provide a third value, the variable z defaults to 0 and uses that value inside the function.

julia> xyzpos(1,2)

1, 2, 0

julia> xyzpos(1,2,3)

1, 2, 3

10 — It can do general-purpose programming

Although Julia is designed as a technical language first, this does not mean that it can’t be used for other things. Just like Python, Julia can also be used for writing software in the widest variety of application domains. This is because Julia does not include language constructs designed to be used within a specific application domain. Julia lets you write UIs, statically compile your code, or even deploy it on a webserver. It also has powerful shell-like capabilities for managing other processes. It provides Lisp-like macros and other metaprogramming facilities. The standard library also provides asynchronous I/O, process control, logging, profiling, and more.

Julia uses multiple dispatch as a paradigm, making it easy to express many object-oriented and functional programming patterns. This allows developers to change the behaviour of functions based on the run-time’s state of more than one of its arguments. This is similar to single-dispatch where a function or method call is dynamically dispatched based on the actual derived type of the object on which the method has been called. Multiple dispatch takes it a step further by routing the dynamic dispatch to the implementing function or method using the combined characteristics of one or more arguments.

Julia also ships with an amazing package manager which is designed around “environments” instead of a single global set of packages like traditional package managers. In Julia, packages can either be local to an individual project, or shared and selected by name. Environments are maintained in a manifest file, containing the exact set of packages and versions which a particular application needs. If you’ve ever tried to run code you haven’t used in a while only to find that you can’t get anything to work because you’ve updated or uninstalled some of the packages your project was using, you’ll understand why such an approach is needed. Thanks to such environments, each application maintains its own its own independent set of package versions. This greatly improves reproducibility, allowing developers to check out a project on a new system, simply materialize the environment described by its manifest file, and immediately be up and running with a known-good set of dependencies.

Bonus — It’s reached 1.0

This is great because this means that the language has reached a state of “fully baked”, and the Julia core contributors have pledged a commitment to language API stability which means that code written to run for Julia 1.0 will continue to work in Julia 1.1, 1.2, etc. This means that the core language developers and community alike can focus on packages, tools, and new features built upon this solid foundation.

Where to go from here

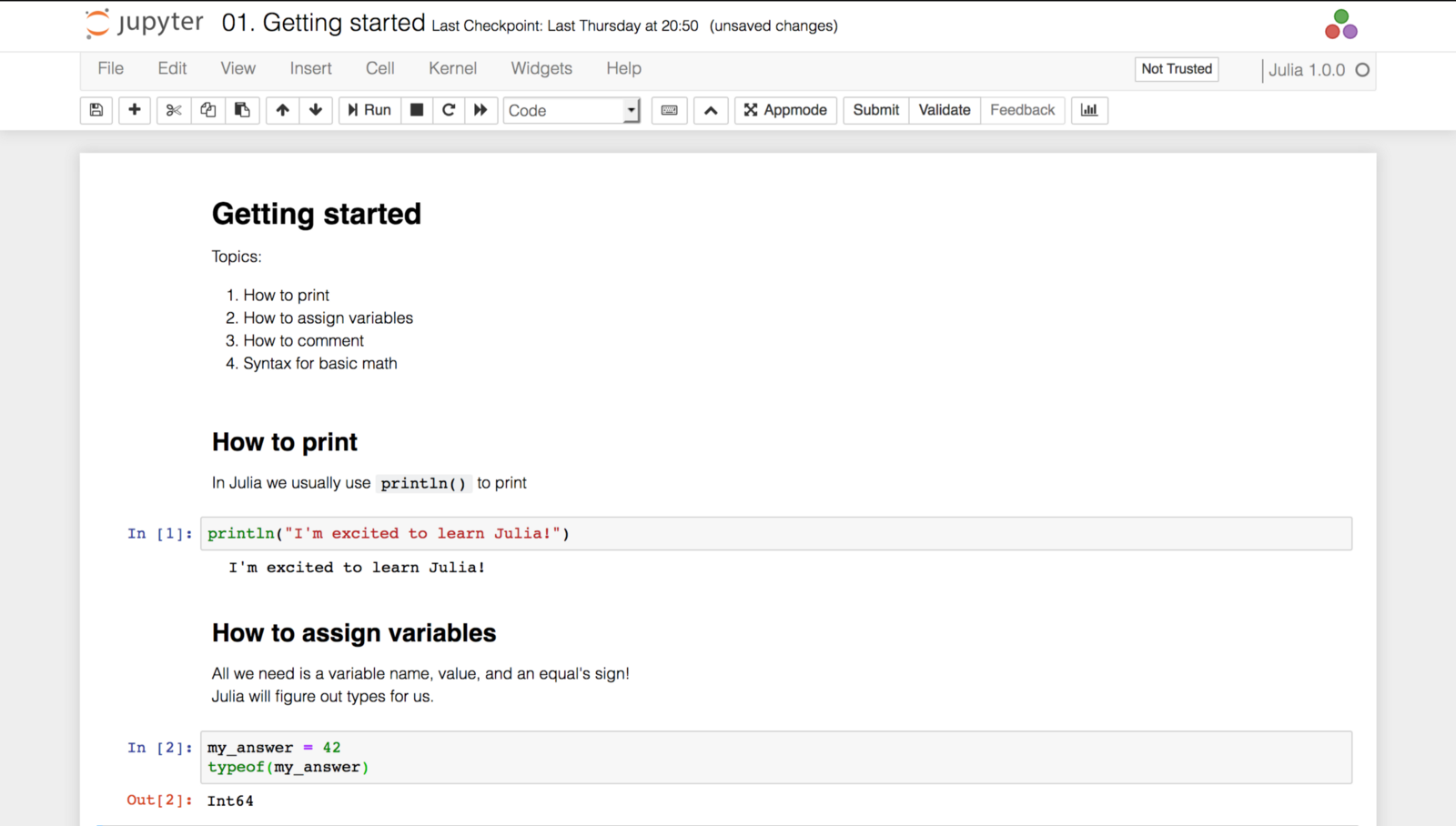

JuliaBox lets developers prototype their Julia code in Jupyter notebooks right in their browser. JuliaBox is the number one choice for universities teaching Julia since students can start using Julia in seconds with no installation required.

JuliaBox has been running continuously since January 2015 at www.juliabox.com and has delighted over 50,000 users. It provides the popular Jupyter notebook interface to run Julia. Many common Julia packages, such as those included in JuliaPro are available by default and other packages can be installed by users. JuliaBox is extremely popular for teaching Julia. It is available free for limited usage today. — juliabox.com

JuliaBox includes a number of introductory tutorials to get you up and running with the language, but also go a step further and include advanced tutorials to get you up to speed with the language’s capabilities.

Getting started tutorials on JuliaBox

Getting started tutorials on JuliaBox